Before I get started, let me make one thing perfectly clear: I love the Olympics. I mean, what’s not to love? In this summer’s Games, for example, we get to see the best athletes in the world competing in 300 events in 35 sports. There are amazing contests of skill, inspiring back stories, and heart-stopping finishes. And best of all, for 16 days, the focus of the world is on something that doesn’t have to do with war, political upheaval, or some other horrible disaster. We’re all in this together, and it’s just plain fun.

But in all honesty, the Olympics are a mess. Take this summer’s games in Rio. From Zika and infrastructure problems to pollution, crime and politics, it’s like a perfect storm of nearly everything that could possibly go wrong. Some athletes have elected not even to attend. And given the situation, I’m not sure I entirely blame them. Really, it’s sad.

Traditionally, cities have vied for the honor of hosting the games. It’s a matter of civic and national pride. The Games provide them with a terrific showcase and can potentially bring in millions of TV and tourist dollars. But in recent years, a growing number of cities are giving them a pass. Oslo, Stockholm, Lviv, and Krakow all withdrew their bids for the 2022 Winter Olympics, leaving only Beijing and the Kazakh city of Almaty in the running, two undemocratic cities with less than stellar human rights records. This is hardly a surprise. Both have autocratic governments that can pretty much spend money as they like, without answering to the public. (Here’s a spoiler alert: Beijing won, and the mountains where the events will be held have an average annual snowfall of less than two inches. Crazy, right?).

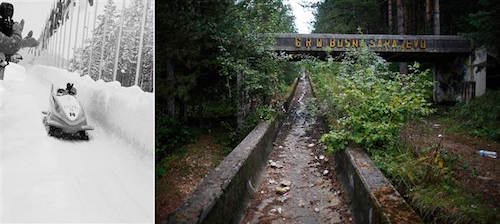

Why the change? A look at previous Olympic sites can give us some insight. Host cities often face corruption, ballooning costs, underinvestment in public services, and projects that don’t help — and sometimes even harm — much of the population. What’s more, the Olympics are not the job creators one might imagine. According to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the Games typically create anywhere from 50,000 to 300,000 jobs, but most are just temporary and go to people who already have work (only 10% of the 48,000 jobs created by the London Olympics, for example, went to previously unemployed people). In the end, host cities are often left with tremendous debt that they usually can’t afford to pay, and white elephant structures that cost too way much to maintain. Photos from Athens, Sarajevo, Sochi, and other locales bear this out, showing crumbling, abandoned structures just a few years after the games.

In a 2006 paper, “Mega-events: The effect of the world’s biggest sporting events on local, regional, and national economics,” Holy Cross economics professor Victor Matheson had this to say:

“Public expenditures on sports infrastructure and event operations necessarily entail reductions in other government services, an expansion of government borrowing, or an increase in taxation, all of which produce a drag on the local economy. At best public expenditures on sports-related construction or operation have zero net impact on the economy as the employment benefits of the project are matched by employment losses associated with higher taxes or spending cuts elsewhere in the system.”

The solution: a permanent Olympic location

It only makes sense. Instead of building new facilities and creating entirely new infrastructures every few years — and incurring millions of dollars in debt — why not build, maintain, and re-use a permanent Olympic venue? This could overseen by the IOC and financed by all participating countries. And as for hosting, the IOC could sell rights to a different country for each Olympic Game, thereby giving the licensee the showcase they would have otherwise enjoyed. Another solution: A decentralized Olympics, with different cities hosting different events. This would result in a more diverse Olympics than we’ve had in the past, create showcases for multiple cities, and spread the cost out over more than one locale.

I’m not an economist, and I surely don’t have the knowledge that’s required to figure this out. But it’s clear that a different approach is needed for the Olympics to remain sustainable. Let’s hope someone comes up with one soon.