Do you have a ski trip planned for this year? I live on the East Coast, and yes, I do plan to hit a big western resort this season — one that has a lot more altitude than what I’m used to here in Vermont.

Does the altitude bother me? Yeah, a bit. For the first few days I might feel a little light headed. I might have trouble catching my breath when I ski. I could have headaches. And I almost always suffer from insomnia (then again, I’m a chronic insomniac at home, too). But after that, I’m usually fine. Yet I have friends who’ve had it a lot worse. One actually ended up in the hospital during a trip to Breckenridge. It was so bad that he refuses to ski out west anymore.

So what is altitude sickness, and why do we have problems?

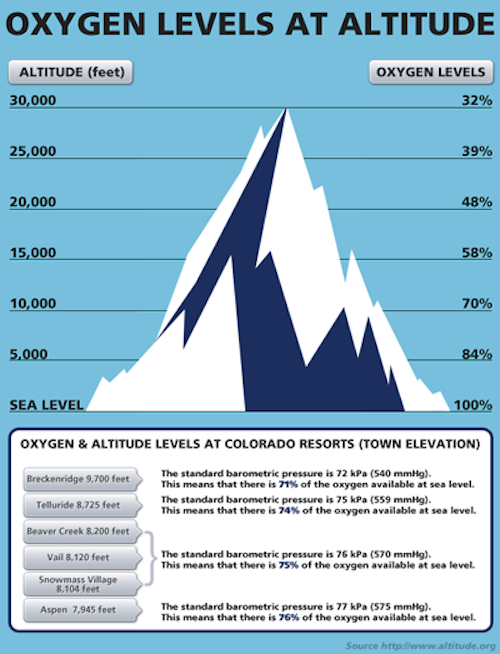

Altitude sickness is a term that covers a variety of health problems caused by reduced air pressure and lower oxygen levels. There’s no way to predict a person’s highest comfortable altitude, and being physically fit isn’t necessarily a protection. Studies show that 25 percent of people demonstrate signs of altitude sickness at elevations as low as 8,000 feet, and three-quarters of us have mild symptoms over 10,000 feet.

Altitude sickness comes in three varieties:

• AMS, or Acute Mountain Sickness. This is the most mild form, and generally involves headache, fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, and occasional vomiting. You usually feel better within 24 to 72 hours.

• HAPE, or High Altitude Pulmonary Edema. This is a dangerous build-up of fluid in the lungs that prevents the air spaces from opening up and filling with fresh air with each breath. Symptoms include headache, dizziness, blurry vision, and disorientation. It’s not that common, but it can become fatal. The only treatment is to get down to a lower altitude.

• HACE, or High Altitude Cerebal Edema. This is a build-up of fluid in the brain, and like HAPE, it can be fatal. Mild symptoms can include a dry cough and shortness of breath after mild exertion, but more severe types of HAPE involve shortness of breath at rest, confusion, and fever. Drowsiness and loss of consciousness occur shortly before death.

Is there a way to prevent altitude sickness?

Altitude sickness can happen to anyone, even if you’ve never had a problem at altitude before, so it pays to be aware of ways to prevent or alleviate the symptoms:

• Acclimate. If you have the time, this is really the best way to go. Gradually increase your elevation by no more than 1,000 ft per day. For most of us, though, this isn’t really practical. But spending a day or two at an altitude higher than you’re accustomed to — yet lower than your final destination — can be a big help.

• Don’t drink alcohol. This might be tough. After all, what’s apres ski without the alcoholic beverage of your choice? Still, it’s better if you lay off for a few days. Alcohol is a vasoconstrictor, which means it constricts the blood vessels that carry oxygen throughout the body. If you’re already suffering from low oxygen levels, then alcohol really doesn’t make sense. Oh, and don’t smoke, either.

• Drink plenty of water. Hydrate, hydrate, hydrate. Your lungs lose more water vapor at high altitudes, and that can contribute to altitude sickness symptoms. Experts recommend drinking two to three liters of water per day.

• Climb High, Sleep Low. This is an old climber’s adage, and it applies to skiers, too. If you want to avoid the symptoms of altitude sickness, don’t sleep at elevation. It’s better to spend the night lower down where the oxygen is richer, while you’re trying to acclimate.

• Ibuprofren. Yep, plain old Motrin or Advil. Researchers report in the Annals of Emergency Medicine that among a group of 86 men and women who spent two days hiking in the White Mountains of California, those who were randomly assigned to receive ibuprofen were 26% less likely to develop acute mountain sickness than those who took a placebo. The ibuprofen group took four doses of 600 mg each in a 24-hour period during which they ascended to 12,570 ft.

• Oxygen Enrichment. If you’re really having problems, taking a hit from a gas canister can make you feel a lot better. Consider it nature’s little pick me up.

• Medications. If you’re affected by altitude sickness or if acclimatization doesn’t work, your doctor may recommend a prescription medication that may reduce the incidence and severity of altitude sickness.